Niebuhr Among His Contemporaries

Niebuhr's interactions with Eliot, Auden, Barth, Graham, Maritain, Lewis, and Ellul.

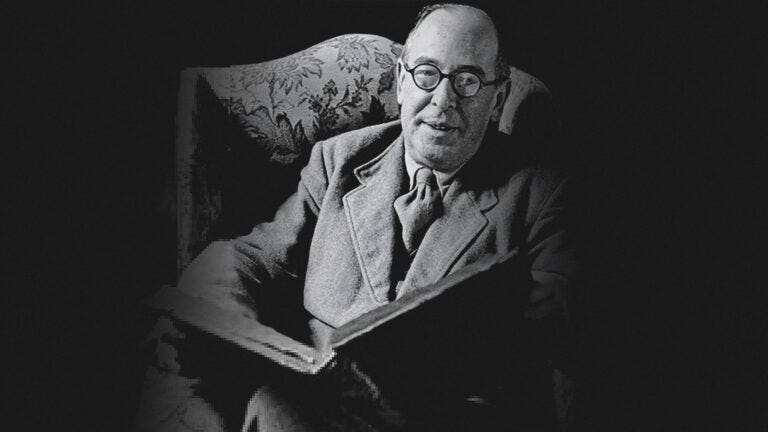

I began an earlier essay for Mere Orthodoxy with a remark made by Jean Monnet, the architect of the United Nations: “Nothing is possible without men, but nothing lasts without institutions.” More and more it seems to me that understanding history’s Great Men and Women requires familiarity with the relationships, connections, and institutions that made their work possible. William Wilberforce’s crusade against the slave trade is mere hagiography apart from an appreciation of the Clapham Sect; J. R. R. Tolkien and C. S. Lewis’ writings make far more sense if you know The Inklings. Alan Jacobs’ The Year of Our Lord 1943 offers just this kind of enmeshed analysis.

"Reinhold Niebuhr, T. S. Eliot, and The Year of Our Lord 1943"

While an excellent book, The Year of Our Lord 1943 turns on a misleading distinction between its protagonists (T. S. Eliot, C. S. Lewis, Jacques Maritain, W. H. Auden, and Simone Weil) and Reinhold Niebuhr.

In my essay, I look at how Eliot himself thought of Niebuhr. From private letters that were released to the public after Jacobs’ book was published, we know that Eliot considered Niebuhr “far and away the best theological thinker in America.”

Since turning in the piece, I learned a couple more interesting things about Eliot’s and Niebuhr’s underexplored relationship:

Eliot, along with W. H. Auden, Jacques Maritain, and others, helped fund the Niebuhr chair at Union upon Reinhold’s retirement.

Reinhold Niebuhr “regularly used [the Four Quartets] as devotional reading,” according to Eliot scholar Bernard Bergonzi.

Niebuhr once acted in a parody of Eliot’s play Murder in the Cathedral.

One of Niebuhr’s final books, The Structures of Nations and Empires (1959), was saved from a far clunkier title (Dominions in Nations and Empires: A Study of the Structured and Moral Dilemmas of the Political Order Relevant to the Perplexities of a Nuclear Age) on the insistence of Eliot, his editor for publication in the United Kingdom—although the subtitle was still twenty-two words in the end.

Niebuhr and W. H. Auden

Auden wrote a generally positive review of Niebuhr’s Christianity and Power Politics in January 1941, though he included something of a knife at the end (which Jacobs uses to frame The Year of Our Lord 1943):

“The danger of being a professional exposer of the bogus [like Niebuhr] is that, encountering it so often, one may come in time to cease to believe in the reality it counterfeits. … Does he believe that the contemplative life is the highest and most exhausting of vocations, that the church is saved by the saints, or doesn’t he?”

Niebuhr welcomes the critique and invites Auden over to explore the issue further (they lived about ten miles apart in New York). They became fast friends and just months later, Auden is already citing Niebuhr’s influence on poems like “At the Grave of Henry James”:

All will be judged. Master of nuance and scruple,

Pray for me and for all writers living or dead; […]

For the treason of all clerks.

Reinhold’s wife Ursula and Auden (both British born) would team up to mock Reinhold, calling him fidgety, making fun of his eating habits, and teasing him as a “Prot.” Reinhold, in turn, referred to the two lovingly as “damned Anglicans.”

As famously as the three got along (many Union students fondly recall encountering Auden at the Niebuhrs’ house), Auden sometimes struggled to be around them. “When I see you surrounded by family and all its problems, I alternate between self-congratulation and bitter envy,” he confessed in one of many exchanged letters.

Niebuhr, Barth, and Billy Graham

Niebuhr’s relationship with Barth went through many ups-and-downs but after World War II, Niebuhr was outraged with Barth’s failure to confront communism and wanted to stem his influence. On Barth and his followers (whom he saw as indifferent to major world affairs), Niebuhr wrote: “Yesterday they discovered that the church may be an ark in which to survive a flood. Today they seem so enamored of this special function of the church that they have decided to turn the ark into a home on Mount Ararat and live in it perpetually." Niebuhr’s beef with Barth was on par with Kendrick vs. Drake, driving major news headlines

Despite having positive things to say about other celebrity preachers like Billy Sunday, Niebuhr had very few kind words for Graham, accusing him of “pietistic moralism.” Niebuhr also blasted Graham for presiding over church services at the White House (a new initiative from Nixon), calling it the “Nixon-Graham doctrine of the relation of religion to public morality and policy,” even going so far as to argue it violated the First Amendment.

Niebuhr, Lewis, Maritain, and Ellul

In 1940, C. S. Lewis writes to his brother that he’s reading Reinhold Niebuhr’s Interpretation of Christian Ethics (1936), calling it “a very disagreeable but not unprofitable book.” Almost two decades later, he writes in another letter that he’s only read one book of Niebuhr’s (presumably the same) and can’t remember the name but “on the whole, reacted against it.”

Reinhold laments in a 1948 letter to Ursula that the “women’s question” (on ordination) is hopeless and “one could not even raise the issue significantly. C.S. Lewis has come to the support in Time and Tide of an Anglican dean who declares that women as priests are impossible."

From 1944 to 1947, “Niebuhr joined Jacques Maritain… and others for a four-to-six hour meeting every six weeks” for the Commission on Freedom of the Press (also known as the Hutchins Commission, for its chair, University of Chicago president Robert Hutchins). The commission was formed by Henry Luce (the publisher of both Time and Life magazines). Perhaps unsurprisingly, then, Niebuhr graced the cover of Time the following year in 1948.

Niebuhr and Jacques Ellul were two of the ten members of the World Council of Churches’ Commission on The Church and the Disorder of Society. The commission, which also included Emil Brunner, issued a major report in 1948.